Beyond the Uniform: Why Police Reform Remains Nigeria’s Hardest Social Bargain

Beyond the Uniform: Why Police Reform Remains Nigeria’s Hardest Social Bargain

Reforming the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) is far more than an exercise in administrative restructuring; it is a delicate negotiation involving power, politics, culture, and the deeper contradictions within Nigerian society. This was the central argument at a high-level workshop for media professionals held in Abeokuta by the Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative, widely known as Partners West Africa Nigeria (PWAN).

The workshop, themed “Reporting on Police Reform and Accountability Issues,” urged journalists to interrogate the deeper forces shaping policing in Nigeria, arguing that the widely referenced “Thin Blue Line” the fragile boundary between order and disorder cannot be strengthened without confronting the society it serves.

Delivering a thought-provoking presentation, Mr. Tosin Osasona, a lawyer, stressed that police reform is a globally contested process, citing experiences from the United States to France. However, Nigeria’s case, he argued, is uniquely complicated by its social structure, political pressures, and cultural expectations.

Delivering a thought-provoking presentation, Mr. Tosin Osasona, a lawyer, stressed that police reform is a globally contested process, citing experiences from the United States to France. However, Nigeria’s case, he argued, is uniquely complicated by its social structure, political pressures, and cultural expectations.

“When you attempt to reform the police, you are ultimately trying to reform society,” Osasona noted.

Since the return to democracy in 1999, successive administrations have established multiple reform panels from the Danmadami Committee to the 2018 SARS Reform Panel. Yet implementation has remained largely elusive, trapped between the political demand for tough security responses and growing calls for human rights-compliant policing.

One of the most striking revelations at the workshop was the extent to which the police have been drawn into non-criminal disputes, creating what experts described as a “crisis of performance” within the force.

One of the most striking revelations at the workshop was the extent to which the police have been drawn into non-criminal disputes, creating what experts described as a “crisis of performance” within the force.

A significant portion of police time and resources, participants heard, is currently devoted to including debt recovery disputes, landlord-tenant conflicts and marital and family disagreements

Experts warned that when law enforcement agencies are routinely used as instruments for social arbitration rather than criminal investigation, their effectiveness as professional security institutions is inevitably undermined.

The workshop also placed Nigeria’s policing challenges within a global context, dispelling the notion that performance gaps are unique to developing democracies.

Statistics shared at the session showed that in the United States, fewer than 10 percent of reported crimes are successfully resolved and n the United Kingdom, less than 3 percent of reported rape cases make it to court.

Against this backdrop, speakers argued that Nigeria’s police are often expected to achieve exceptional results despite limited resources, weak institutional support, and persistent misuse by members of the public to settle personal scores.

PWAN disclosed that, with support from the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), it is implementing a nationwide project across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones titled: “Enhancing Public Trust and Gender-Responsive Policing in Nigeria Through the Effective Implementation of the Police Act.”

As a women-led organization, PWAN emphasized the need for reforms grounded in humanitarian sensitivity, particularly in addressing the needs of women, children, and other vulnerable groups within the justice system.

Despite acknowledging that the road to reform remains “steep and rough,” participants identified emerging signs of progress within the Nigeria Police Force.

Key among them are an increase in the dismissal and “de-kitting” of erring officers, signaling a gradual departure from the long-standing culture of institutional cover-ups, growing willingness by police authorities to engage journalists in constructive dialogue about modern policing standards and accountability

The workshop concluded with a strong call to action for journalists, urging them to move beyond episodic, “he-said-she-said” crime reporting.

Media professionals were challenged to anchor their reporting on the Police Act, interrogate institutional bottlenecks, and sustain public scrutiny that can help transform the Nigeria Police Force from a social dispute-settling agency into a professional, intelligence-driven investigative institution.

As speakers agreed, without a corresponding reform of societal expectations, police reform in Nigeria may remain the country’s most difficult, yet most necessary and negotiation.

What's Your Reaction?

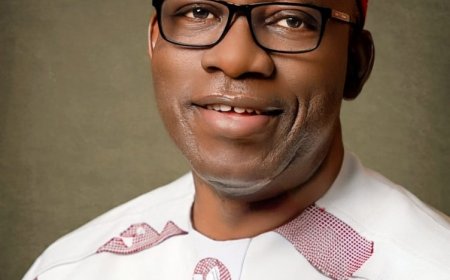

The Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Adron Homes and Properties Limited, Aare Adetola Emmanuelking, has congratulated the Government and people of Oyo State as the state marks its 50th anniversary, describing the occasion as a celebration of resilience, cultural pride, and sustained progress.

The Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Adron Homes and Properties Limited, Aare Adetola Emmanuelking, has congratulated the Government and people of Oyo State as the state marks its 50th anniversary, describing the occasion as a celebration of resilience, cultural pride, and sustained progress.